A retired B&O trainman related an incident where a worktrain was in the area and during the night backed onto this structure. A sleepy inhabitant of one the cars got up to relieve himself, hopped off the step and fell into the river below.

I read recently that railroad property in Oakland was destroyed by the Jones-Imboden raid of 1863. Whether this bridge was a casualty was not clear in the book B&O in the Civil War by Festus Summers. Other sources say that the wooden bridge was destroyed in one of at least two Confederate raids during the war.

An Incident Involving 88 Bridge-Excerpted from “A Tragic Freight Train Wreck”

Robert Garrett’s father was an apprentice telegrapher in Oakland when he witnessed a freight train plow into the back of a stopped freight just west of Oakland on July 28, 1882. The first freight had stopped when the air brakes went into “emergency”, most likely because of a broken air hose(2). A flagman(3) was immediately sent back to stop any following traffic, however the flagman’s efforts were in vain as a following freight could not stop in time and hit the caboose of the stopped train, resulting in the death of a drover(4) who did not clear the area in time. Robert Garrett learned the rest of story some 75 years later when a old conductor told why the flagman was not successful.

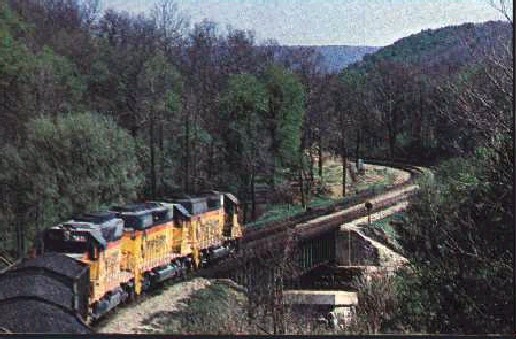

Robert Garrett tells the story, “The flagman who went back to protect his train that July night so long ago was afraid of ghosts. For that reason he did not even go as far as No. 88 Bridge, whereas for proper protection he should have crossed and gone a considerable distance west of the bridge. For many years the bridge was of the truss design, with overhead framework which caused the death of many brakemen(5) and other who happened to be standing on top of boxcars as the train passed over the bridge. Suitable warning devices(6) were provided on both sides of such bridges, of course, but occasionally an accident occurred.

Some of the the men who over the years met death at this bridge were “tramps”, a type common many years ago along the railroads, but now practically if not completely extinct. Having no friends or relatives, such victims of the bridge sometimes were buried without benefit of religion along the right of way. The writer recalls seeing several graves at that point, many years ago, each marked with a rude cross doubtless put there by the burial party of section hands. These lonely graves since have been completely covered by ballast and waste material dumped along the tracks by repeated maintenance operations. For the superstitious, it doubtless required but little imagination to people the spot with ghosts. The Flagman was of that type, and although fully aware of the danger to his train by reason of a “short flag”, he nevertheless just could not force himself to cross that bridge at midnight. The disastrous, fatal wreck was the result."

(1) Garrett, Robert. “A Tragic Train Wreck” The Glades Star (Garrett County Historical Society). Volume 3 No. 14, September, 1963.

(2) One of the fascinations of railroading is the physics of stopping a mile-long train weighing thousands of tons traveling at mainline speed. Normal experience with an automobile’s brakes cannot be applied to a train:, a train is a locomotive pulling device followed by up to a hundred and fifty coupled but separate cars. For the first 50 to 75 years of railroading, trains were stopped by human force (see below). The genius of the Westinghouse air brake design is a real life example of” thinking out of the box” and might have been invented by a Garrett Countian. Air brakes could be designed where compressed air directly from the locomotive’s compressor would apply the brakes to each car by means of pipes and connecting flexible hoses (the so-called “train line”). The problem with this system is that trains are often intentionally or unintentionally separated. This system would leave the back portion of the separated train without brakes, a extremely dangerous situation. Westinghouse designed a system where each car has a compressed air tank that is pumped up by the train line. When full, an automatic valve on each car is shut by a certain pressure from the train line, keeping the compressed air in the tank. When application of brakes is needed, the locomotive engineer reduces the pressure in the train line, which allows the valve to open in a position that supplies compressed air to the brakes on each car’s wheels. Various pressures reductions result in increasing braking effort up to full reduction (in railroad slang “big holing it”), which puts the brakes into “emergency”. So, as in the case above, a broken air hose causes full train line reduction and the train comes to a stop with all brakes applied. Although a problem when the train is on the level, this braking system is a lifesaver when a train is on an upgrade, otherwise, as mentioned above, the back of train would roll back down the hill.

(3) Up until recent times, a flagman stationed at the rear of the train was an absolute necessity. In early railroading, trains ran on timetables ( a matrix that rules where a scheduled train should be at any given time) and train orders (where a dispatcher figures out where scheduled traffic is and weaves in “extras” to optimize traffic flow). In the 1880’s locomotive power and braking limitations dictated that trains were shorter but also much more frequent. On a busy mainline like the B&O before automatic signaling, a stalled train was likely to be rammed by the always present following train. It was the flagman’s job to hustle back a prescribed distance from any stopped train and flag down the following train. The train in the account above was stopped because of a broken air line hose. In that case, first the crew had to find the break, then fix it and finally pump up the train line. The time involved in these processes almost insured that a following train would arrive and need to be stopped, so this particular flagman’s fear of ghost was truly powerful. A final note on the flagman’s role before two way radio communications. When the train was ready to proceed, the engineer gave a certain whistle signal to call back the flagman. Remember, the flagman and engineer could be a mile or more apart and could not talk to each other. The flagman needed to light a timed fusee to warn approaching trains in his absence and then hustle back to the caboose. When hand signals from the caboose was not possible (because of curves, fog, etc), the engineer had to guess how long it would take for the flagman to return before proceeding. If the flagman was tardy in returning, the conductor in the caboose could reduce the train line pressure and again stop the train, causing the air pump-up process to start over, or the conductor could choose to leave the flagman behind to fend for himself. Cabooses and flagmen have been eliminated in today's mainline railroad by electronic "end of train devices" that send out a message to warn off a following train.

(4) The drover died a horrible lingering death after being trapped underneath the steam locomotive that slammed into the caboose. One wonders why the drover had not cleared out of the caboose long before the wreck. Perhaps the drover was not a railroad employee, but was hired by the livestock owner. When the rest of the crew left to find the broken air hose, they left the drover to sleep, another bad lapse of judgement.

(5) The job of the brakeman in hand braking days was incredibly dangerous. Each rail car has a system to manually apply the brakes by turning a hand wheel. Before airbrakes, two brakemen, one at the front of the train and one at the back, would walk from car to car applying brakes on a certain whistle signal from the engineer, using catwalks built on top of box cars. On another signal, the brakeman would loosen each car’s brakes when the engineer judged that brakes where no longer needed. Brakemen were expected to ride out on the train in all weather (rather than be in the warm cab or the caboose) so as to be immediately prepared to apply brakes. One who has experienced a Garrett County winter can barely imagine how brakemen survived riding out in the frigid temperatures, let alone hopping from icy car to icy car. As described in the account above, another danger was low clearances that could kill the brakeman outright or could knock him off to be run over by the train. The brakeman might only be missed the next time brakes needed to be applied and he was no longer on the train! A puzzle to me is how empty open top hopper cars were handbraked, how did the brakeman get from car to car? Rail cars still have hand brakes, so as to able to lock down the brakes when the car is parked in a siding. Long ago, the rooftop catwalks were banned to keep the crew off the top of the cars.

(6) The device to warn of an approaching low clearance is called a telltale. It usually consisted of a wire strung between two poles; from the wire hung other wires or other light material that would brush the person riding on top of the car to warn him to lie flat. Some telltales are still in existence along right of ways.

(7) For another wreck involving brakes go to

Big Savage Wreck page.

From Tall Pines and Winding Rivers-Benj.Kline |

Preston Railroad |

Castleman River Railroad |

Garrett County Coal |

Operating Coal Loaders 2001 |